How the Fed Affects Individual Investors

It was just a few months ago when the financial community was certain the Federal Reserve would continue raising interest rates. But, in a speech earlier this year, the Vice Chair of the Fed noted,

“The U.S. economy enters 2019 after a year of strong growth, with inflation near our 2 percent objective, and with the unemployment rate near 50-year lows.

That said, growth and growth prospects in other economies around the world have moderated somewhat in recent months, and overall financial conditions have tightened materially. These recent developments in the global economy and financial markets represent crosswinds to the U.S. economy.

If these crosswinds are sustained, appropriate forward‑looking monetary policy should seek to offset them to keep the economy as close as possible to our dual-mandate objectives of maximum employment and price stability. As we have long said, monetary policy is not on a preset course.”

Source: Federal Reserve

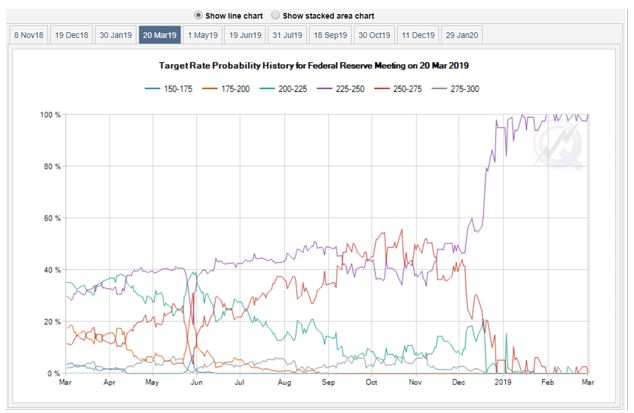

Clarida’s comments indicated the Fed is not determined to raise rates and could cut them when the data dictates. Traders are now incorporating this view into market prices as the chart below shows.

Source: CME

This is a chart of expected action by the Fed. In October a majority of traders believed the Fed would raise rates at their march meeting. Now, there is almost complete agreement rates will remain unchanged at that meeting.

This is all important to the economy and the market. It is also important to individual investors.

How Monetary Policy Affects Investors

According to economists working with the San Francisco branch of the Federal Reserve “the point of implementing policy through raising or lowering interest rates is to affect people’s and firms’ demand for goods and services.

For the most part, the demand for goods and services is not related to the market interest rates quoted in the financial pages of newspapers, known as nominal rates. Instead, it is related to real interest rates—that is, nominal interest rates minus the expected rate of inflation.”

This measure is shown in the next chart.

Source: Federal Reserve

The recent move into positive territory could be a concern for the Fed. This interest rate affects individuals, because, as the Fed explains,

“For example, a borrower is likely to feel a lot happier about a car loan at 8% when the inflation rate is close to 10% (as it was in the late 1970s) than when the inflation rate is close to 2% (as it was in the late 1990s).

In the first case, the real (or inflation-adjusted) value of the money that the borrower would pay back would actually be lower than the real value of the money when it was borrowed. Borrowers, of course, would love this situation, while lenders would be disinclined to make any loans.”

But the Fed doesn’t directly set the rate for car loans,

“Remember, the Fed operates only in the market for bank reserves. Because it is the sole supplier of reserves, it can set the nominal funds rate.

The Fed can’t set real interest rates directly because it can’t set inflation expectations directly, even though expected inflation is closely tied to what the Fed is expected to do in the future.

Also, in general, the Fed has stayed out of the business of setting nominal rates for longer-term instruments and instead allows financial markets to determine longer-term interest rates.

Long-term interest rates reflect, in part, what people in financial markets expect the Fed to do in the future.

For instance, if they think the Fed isn’t focused on containing inflation, they’ll be concerned that inflation might move up over the next few years. So they’ll add a risk premium to long-term rates, which will make them higher.

In other words, the markets’ expectations about monetary policy tomorrow have a substantial impact on long-term interest rates today. Researchers have pointed out that the Fed could inform markets about future values of the funds rate in a number of ways.

For example, the Fed could follow a policy of moving gradually once it starts changing interest rates. Or, the Fed could issue statements about what kinds of developments the FOMC is likely to focus on in the foreseeable future; the Fed even could make more explicit statements about the future stance of policy.

Changes in real interest rates affect the public’s demand for goods and services mainly by altering borrowing costs, the availability of bank loans, the wealth of households, and foreign exchange rates.

-

For example, a decrease in real interest rates lowers the cost of borrowing; that leads businesses to increase investment spending, and it leads households to buy durable goods, such as autos and new homes.

-

In addition, lower real rates and a healthy economy may increase banks’ willingness to lend to businesses and households. This may increase spending, especially by smaller borrowers who have few sources of credit other than banks.

-

Lower real rates also make common stocks and other such investments more attractive than bonds and other debt instruments; as a result, common stock prices tend to rise. Households with stocks in their portfolios find that the value of their holdings is higher, and this increase in wealth makes them willing to spend more. Higher stock prices also make it more attractive for businesses to invest in plant and equipment by issuing stock.

In the short run, lower real interest rates in the U.S. also tend to reduce the foreign exchange value of the dollar, which lowers the prices of the U.S.-produced goods we sell abroad and raises the prices we pay for foreign-produced goods. This leads to higher aggregate spending on goods and services produced in the U.S.

The increase in aggregate demand for the economy’s output through these different channels leads firms to raise production and employment, which in turn increases business spending on capital goods even further by making greater demands on existing factory capacity. It also boosts consumption further because of the income gains that result from the higher level of economic output.”

These may sound indirect but as BankRate.com notes, “When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, you feel it.

“The Federal Reserve has its fingers in your pocketbook to a greater degree than the IRS,” says Michael Reese, a certified financial planner.”

Did you know that dividends have rewarded investors for at least 100 years, at least since John D. Rockefeller said, “Do you know the only thing that gives me pleasure? It’s to see my dividends coming in.”

We have prepared a special report about dividends that you can access right here.