Investors Need to Listen to This Nobel Prize Winner

Economists often focus on theory. A popular economic theory is the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). The Nobel Prize winning economist says there are two important pieces of the EMH.

First is the fact that there is no free lunch in the stock market. By this, Thaler means that potential returns are tied closely to the potential risks. If you are seeking higher than average returns, you must accept higher than average risks. On this point, there is really no significant disagreement.

The second aspect of the EMH that Thaler emphasizes is the fact that the theory contends the current market price is always correct. On this point, there is ample room for disagreement.

Theoretical Pricing Models Seem Correct

This point does have a compelling underlying logic. There is no one person that has all of the information related to a specific stock price. Each investor has some information and each investor also has an opinion about that information.

The market price of a stock reflects all of the available information and represents the collective view of all potential investors.

Market prices are determined in an auction process. Bidders announce what they will pay and sellers set the lowest price that they will accept. The current price results from a meeting of the minds between actual buyers and sellers.

It does make sense that the current price should reflect what buyers and sellers using all of the available information are willing to buy or sell at. However, the market price moves constantly and the current price will drift away from the fair value.

At times, the drift will be significant. One technique to measure drift was developed by another Nobel Prize economist.

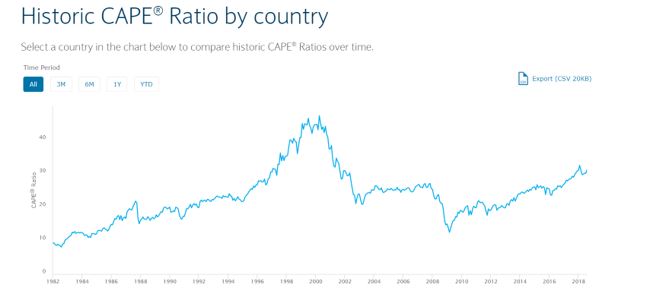

CAPE Measures Value

Robert J. Shiller, a 2013 Nobel laureate in economics, is Professor of Economics at Yale University and the co-creator of the Case-Shiller Index of US house prices. He is the author of Irrational Exuberance, the third edition of which was published in January 2015, which detailed an approach to measuring value.

At Project Syndicate, Shiller recently noted, “The US stock market, as measured by the monthly real (which means it is adjusted for inflation) S&P Composite Index, or S&P 500, has increased 3.3-fold since its bottom in March 2009. When inflation is considered the index has increased by 4.4 times.

This makes the US stock market the most expensive in the world, according to the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio that I have long advocated. Is the price increase justified, or are we witnessing a bubble?”

Source: Barclays

Right now, CAPE is well above average.

Shiller Puts CAPE In Context of Earnings

There are reasons to expect CAPE to be high. Shiller notes, “One might think the increase is justified, given that real quarterly S&P 500 reported earnings per share rose 3.8-fold over essentially the same period, from the first quarter of 2009 to the second quarter of 2018. In fact, the price increase was a little less than equal to earnings.

Of course, 2008 was an unusual year. What if we measure earnings growth not from 2008, but from the beginning of the Trump administration, in January 2017?”

Over that 20-month interval, real monthly US stock prices rose 24%. From the first quarter of 2017 to the second quarter of 2018, real earnings increased almost as much, by 20%.

With prices and earnings moving together on a nearly one-for-one basis, one might conclude that the US stock market is behaving sensibly, simply reflecting the US economy’s growing strength.

But it is important to bear in mind that earnings are highly volatile. Sudden sharp increases tend to be reversed within a few years. This has happened dramatically more than a dozen times in the US stock market’s history.

History Provides Precedents

Shiller points to the time around World War I as a time when earnings grew quickly.

“Consider an example from a century ago. Although real S&P Composite annual earnings rose 2.6-fold in just two years, from around trend in 1914 to a record high in 1916, stock prices rose only 16% from December 1914 to December 1916.”

It’s important to remember that Shiller discounts for inflation. The nominal price of the Dow more than doubled over that time.

But, much of that gain came from inflation. It’s important to remember that inflation can increase stock prices even if an investor’s real wealth fails to keep pace.

Shiller also highlighted stock prices after the war.

“Market reaction to earnings increases was much more positive in the “roaring twenties.” After the end of the 1920-21 recession, real annual earnings, which had been depressed by the downturn, increased more than fivefold in the eight years to 1929, and real stock prices increased almost as much – more than fourfold.

What was different about the 1920s was the narrative. It wasn’t a foreign war story. It was a story of emergence from a “war to end all wars” that was safely in the past.

It was a story of the liberating spirit of freedom and individualistic fulfillment. Unfortunately, that spirit did not end well, with both stock prices and corporate earnings crashing catastrophically at the end of the decade.”

Negative sentiment can be a drag on the stock market. His example is within recent memory.

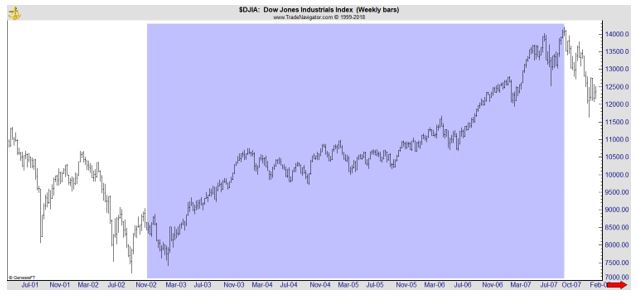

“Then, from 2003 to 2007, during a period of gradual recovery following the 2001 recession, real corporate earnings per share almost tripled.

But the real S&P 500 less than doubled, because investors apparently were unwilling to repeat their mistake in the years leading to 2000, when they overreacted to rapid earnings growth. Nonetheless, this period ended with the financial crisis and another collapse in earnings and stock prices.”

What That Says About the Current Environment

Shiller concludes that, “Apparently, investors believe that this boom is going to last, or at least that other investors think it should last, which is why they are bidding up stock prices in a dramatic response to the earnings increase.

The reason for this confidence is hard to pin down, but it must be rooted in the public’s loss of healthy skepticism about corporate earnings, together with an absence of popular narratives that tie the increase in earnings to transient factors.

Talk of an expanding trade war and other possible actions by a volatile US president just does not seem strongly linked to talk of earnings forecasts – at least not yet.

A bear market could come without warning or apparent reason, or with the next recession, which would negatively affect corporate earnings. That outcome is hardly assured, but it would fit with a historical pattern of overreaction to earnings changes.”